There are many stories spanning centuries and continents about human-dolphin interaction. However, over the last year or so, I’ve come across a number of specific instances from around the world where oceanic dolphins (which includes orcas and psuedorcas) have been recorded (or believed to be) assisting humans with hunting and fishing in one way or another.

Here’s a brief summary of five fascinating cases from Brazil, India, Australia and Costa Rica:

Case 1: Laguna, Brazil

The most well-known example is found in Laguna, Brazil where bottlenose dolphins and local fishers have formed a remarkable system of cooperation. This particular interaction features on BBC’s Ocean Giants1 documentary and an extract can be viewed below:

Case 2: Orissa, India

At the International Congress of Conservation Biology in 2011, I attended a presentation titled: Traditional Ecological Belief Systems: Assessing the role of cultural filters in driving positive perceptions between fishers and dolphins (D’Lima et al. 2011). The study focused on the overlap in the use of space and resources between the local fishers and the endangered Irrawaddy dolphin at Chilika lagoon, and the attitudes of fishers towards the dolphins’ presence.

The researchers found that that traditional fishers (those active for several generations) who fished in areas frequented by dolphins were significantly more positive in their attitudes toward the Irrawaddy dolphins compared with non-traditional fishers (new entrant fishers), who were more neutral. D’Lima and co-authors found that:

“These positive attitudes were linked to firmly held mythologies and beliefs that dolphin foraging augments fish catch. Our study indicated that dolphins spent ~30% of their activity budget barrier-foraging at stake nets, and the presence of foraging dolphins coincided with a significantly higher catch income (per unit effort), and with a higher CPUE of mullet…”2a

Irrawaddy dolphins have a seemingly mutualistic relationship of co-operative fishing with traditional fishers, and are inextricably linked with their fishing activities as well as being of deep mythic and cultural importance. Fishers recall times when they would call out to the dolphins to drive fish into their nets2b. The same interaction has been recorded in the upper reaches of the Ayeyawady River, Burma where Irrawaddy dolphins drive fish towards fishers using cast nets in response to acoustic signals from the fishers. In return, the dolphins are rewarded with some of the fishers’ by-catch. Historically, Irrawaddy River fishers claimed particular dolphins were associated with individual fishing villages and chased fish into their nets2c. How this mutualism affects the behaviour and survival of the dolphins remains unclear2b, although some reports suggest 50% of mortality may be due to being caught in gill nets2d.

Fishing at Chilika lagoon (Image: © Ingetje Tadros www.ingetjetadros.com)

Case 3: Eden, Australia

A few months ago, Australia Geographic published an article about the possible return of orcas (killer whales) to the New South Wales coast. Eden was famous for its orcas back in the 1800s where legend has it that they helped local whalers capture and kill their target species.

The article writes:

Eyewitnesses talked of orcas prowling the entrance of Twofold Bay for migrating humpback, blue, southern right and minke whales. Using the unique geography of the bay, the waiting orcas would ambush whales that were vastly bigger than themselves – ripping at fins, diving over their blowholes, and forcing them into shallower waters for the whalers to finish off. Once a whale was dead, they’d feast on the lips and tongue, leaving the rest of the carcass for the whalers. Over the years baleen whale numbers plummeted, and by the time when Eden’s whaling operation shut down in 1929 orcas were rarely seen. More than 80 years on, it is difficult to know whether the hunting partnership was real. Accounts from the time suggest it was – eyewitnesses described killer whales ‘tail-flopping’ and breaching to attract the whalers; others claimed the predators towed the whaleboats to the flailing whales by tugging ropes with their teeth…the relationship was probably mutual exploitation.3

Case 4: Moreton Bay, Australia

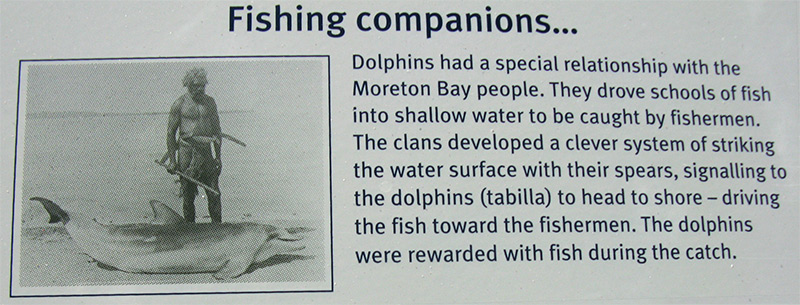

Moving north to Queensland’s Moreton Island and atop of Mt. Tempest (the highest stabilized sand dune in the world at 280m), there is interpretative signage which introduces Moreton Bay’s (‘Quandamooka’) fascinating Aboriginal history. In particular, the people of the ‘Dolphin clans’ reportedly lived in peaceful and harmonious existence with land and sea. The signage reads: 4

Case 5: Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica

The final but possibly most intriguing case comes from the Osa Peninsula, Costa Rica. This story involves ‘pseudorcas’ (false killer whale) , the third-largest members the oceanic dolphins (family Delphinidae) after orcas and pilot whales. According to local guide Shawn Larkin Strunz, of all the whales and dolphins seen in Costa Rica, pseudorcas seem to be the least fearful and most curious toward people.

What makes psuedorcas particularly fascinating is that they are occasionally known to give ‘fish gifts’ to people in the waters off the Pacific coast of the Osa Peninsula. Larkin Strunz writes:

Some people have accepted the gifts; others did not understand a fish was being offered. Once, a fish had to be returned …

Heading back to Isla del Caño… we were having a normal classic session with some pseudorcas, the giant dolphins leaping and surfing around our slow motoring boat. The animals began blowing bursts of bubbles all around the boat, so we stopped to see what they were up to. One pseudorca swam over to the boat with a large, injured big-eye jack in its mouth. Several animals blew massive bubble fountains around the boat, and the one carrying the jack released it under the boat. I filmed the animals with the jack under the boat for a moment, and then one took the jack in its mouth again and held it at the surface next to the captain.

Wild animals that bring fish to humans. A psuedorca in Osa Costa Rica bring gifts of fresh fish to Costa Cetacea chief guide Shawn Larkin. Why do you think that they do this?

The captain took the fish from the pseudorca. The animals blew bubbles. Then we remembered we were in Isla del Caño Biological Reserve waters, where fishing or taking anything is illegal. No ranger would accept the excuse that a giant dolphin gave us the jack; we could be in big trouble, and perhaps lose our license to guide at Caño. Put the fish back, we decided. The captain put the fish in the water and the pseudorca swam back over.

The dolphin blew a large bubble signal and then slowly approached the fish. Ever so gently it reached over, opened its massive jaws and delicately took the gift back and swam away. The other pseudorca, which had stayed alongside the whole time, blew a minuscule bubble trail and swam off with its companion.

Are they giving gifts as a tribute for hunting in “our” waters? Or are they trying to trick us to into boating around and burning fuel to make nice surfing waves for them? Who is the ignorant savage? Is it right or wrong to accept gifts from the giant dolphins? Did we offend the animals by refusing the gift at Isla del Caño? 5

Perhaps Charles Darwin and his successors got it a bit wrong here: evolution is not only about competition but is just as much about cooperation between species. Or is there even more to it than that?

If you have heard of any other stories where dolphins or other wildlife have assisted human hunting and/or why they might do this, let us know at info@eyes4earth.org or join the conversation on Facebook.

References:

Be the first to share a comment