Take a look at this photo and what do you see?

A lioness? Correct.

Sweeping savannah of the Serengeti? Correct.

Anything else?

How long did it take you to spot the collar on this wild lioness?

Don’t berate yourself if you missed it, because you would not be the only one.

I was reminded of this story when I was writing about the influence of alien (non-native) species on (meaningful) nature experience as part of my PhD dissertation. These results re-emphasize how malleable our perception is and that we really do ‘learn to see’.

Or, in the words of Edgar Schein:

We do not think and talk about what we see; we see what we are able to think and talk about.

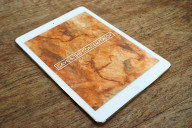

So the story behind this stunning photo (and what was likely a meaningful nature experience for the persons involved, until I accidentally ruined it for them) goes something like this:

Whilst staying at a backpackers in Cape Town, I got chatting to a German couple filled with envy-filling stories of their African travels. The woman was about to show some photos on her laptop so I peered over her shoulder at the screen.

“Wow. Awesome photo there on your desktop background,” I exclaimed. “Where was that photo taken?”

“Ja, it was when we were in the Serengeti. It was one of my favourite moments. We were driving in the afternoon and there was a lioness out all alone. It was so special just seeing it lying there in this vast landscape. It is a beautiful photo.”

I bent forward and to examine the image. “Huh. That’s funny. It’s got a collar on it.”

“A what?”

“A tracking collar.”

“Where?

“There – around its neck,” I pointed. “You hadn’t seen that?” I inquired, a little puzzled.

The girl peered at the lioness, her nose only inches from the screen.

“Are you sure?” She wasn’t convinced.

“Yeah, I’m pretty certain.”

“Hang on. I think I have another photo because it walked right beside our car afterwards.”

She pulled up the other photo (pictured below)

“Yep, there it is!” I remarked a little too gleefully.

“Ah yes, now I see. But you can hardly notice it.” She remarked rather self-consciously.

And in that instant her demeanour changed. She asked me about its purpose and I briefly explained what I knew about wildlife tracking through the use of telemetry. I observed her as she continued looking for photos and I gradually had the feeling that I had interfered with what might have been a meaningful nature experience for her and her boyfriend. Clearly, in the wonder of the moment her perception had somehow ‘edited out’ the collar. And even having this image as a desktop background, she still had not noticed it since.

Interestingly, this somewhat counters against research which has found that Westerners are usually more prone to fixating on focal objects whilst ignoring background and contextual information. But this lady’s observations nevertheless lend support to selective attention research by Simons and Chabris (resulting in the highly viewed “invisible gorilla” video experiment) which shows that we perceive what we look for and remain blind to what else might be there. In this case, this woman might have been looking for that totally wild lion of Serengeti plains and was not able to perceive anything else.

“Does seeing that collar change the experience for you?” I queried.

(If I had not already impacted the memories of this innocent German backpacker, sure as daylight that question must have, although that was not my intent. After all, I was just a curious researcher of profound wildlife encounters. And I was aware at that point that perceptions of “wildness” “naturalness” and “authenticity” are qualities which are conducive to fostering meaningful nature experience – and may detract from it when they are not present).

“No, um, I mean, the lion is still wild isn’t it? It can go where it wants, ja?”

“Yeah, for sure. This is just a monitoring device, so they can learn about its movements and home ranges.”

I explained to her my reason for asking: that I was researching these profound types of encounters and curious to know what factors might affect such experiences.

This event occurred during the early days of my doctoral research and I doubt I did a great job with my explanation.

At that moment her boyfriend entered the room and she showed the collar to him. He leaned into the screen, momentarily tried to pretend he did recall seeing it but then acknowledged he had not and thereafter did not show much further interest at all and went on preparing their dinner.

Had this bit of truth inadvertently snuffed the specialness of experience for them?

And should I feel remorse about that?

Hmmm… truth: it’s a fine line.

References:

Chua, H. ., J. . Boland, and R. . Nisbett. 2005. Cultural variation in eye movements during scene perception. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 35:12629–12633.

Masuda, T., M. Akase, and R. M.H.B. 2008. Cultural differences in patterns of eye-movement: Comparing context sensitivity between the Japanese and Westerners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 94:365–381.

McRaney, D. 2011. You are not so smart. Dutton, Penguin Group (USA) Inc., New York.

Simons, D., and C. Chabris. 1999. Gorillas in our midst: Sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events. Perception 28:1059–1074. See also: http://www.theinvisiblegorilla.com/gorilla_experiment.html

Be the first to share a comment