A recent survey of scientists’ opinions on the state of global biodiversity and its management provides insight into the values which drive the conservation agenda. However, the findings raise an uncomfortable question: Are these opinions actually detrimental in fostering conservation outcomes?

The results, published in the Conservation Biology journal, were designed to elicit opinions of conservation scientists. The author, Rudd (2011:1165), summarizes the key findings as follows:

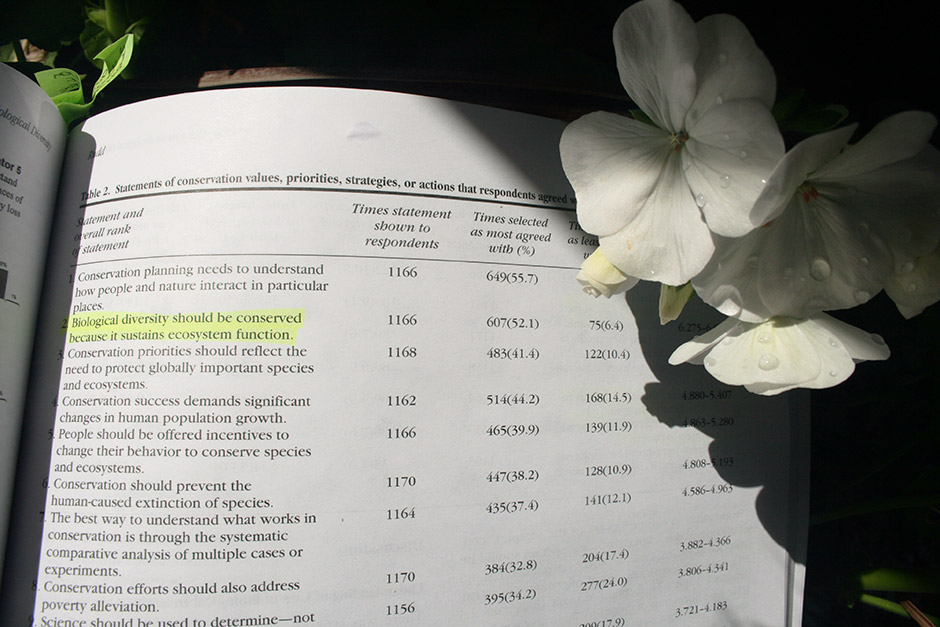

With regard to conservation strategies, scientists most often viewed understanding how people and nature interact in certain contexts and the role of biological diversity in maintaining ecosystem function as their priorities. Protection of biological diversity for its cultural and spiritual values and because of its usefulness to humans were low priorities, which suggests that many scientists do not support the utilitarian concept of ecosystem services.

Paradoxical Priorities

There are a number of striking contradictions amongst the survey results. Primarily, it rests on prevailing beliefs concerning human-nature interaction.

Scientists were in highest agreement with the statement: Conservation planning needs to understand how people and nature interact in particular places (Ranking 1st of 32 statements; No. times Most Agreed with (MA) = 55.7%; No. times Least Agreed with (LA) = 4.2%; No. times statement shown to respondents (n) = 1166).

Yet only a minority found agreement with: Biological diversity should be conserved because of its cultural and spiritual value. (27th ; MA = 9.1%; LA = 30.9%; n = 1161).

This immediately alerts us to somewhat of a dichotomy. As stated by Cocks et al (2012:1):

Conservation is not merely a matter of appropriate conservation technologies and management processes. It is a process that is inextricably bound up with people’s values and world views on nature.

In certain contexts, that interaction is fuelled by cultural and spiritual values, traditionally often in favour of biodiversity protection (Cocks et al. 2012). And yet scientists widely scored these values as low priority, even though international treaties and documents (e.g. CBD, IUCN and UNESCO) all recognize the importance of “biocultural diversity” (Cocks et al. 2012).

What does this potential paradox suggest? Does it mean scientists are willing to go to great lengths to understand people’s interactions with nature but, should it not align with their views on why we should conserve, it will subsequently be deemed unimportant or low priority?

Scientists were in high agreement to the statement: “Biological diversity should be conserved because it sustains ecosystem function.” (2nd ; MA = 52.1%; LA = 6.4%; n = 1166).

In stark contrast – and ranking second to last and third to last respectively – was widespread disagreement to: “The value of biological diversity depends on its usefulness to people”. (31st; MA = 7.6%; LA = 58.1%; n = 1157) and “Biological diversity should be conserved because of the beauty of nature” (30th ; MA = 5.9%; LA = 45.5%; n = 1164).

Given that alternative interpretation of the statements may be possible. these results are understandable. But paradoxically they may provide a disturbing indictment on the current state of conservation affairs.

Beauty and the Beast

These results are predictable in the sense that the general public’s preoccupation with nature’s aesthetics and its usefulness is the bane (and fuels the disdain) of many conservation scientists, and is perceived to be at odds with efforts to preserve biodiversity.

This can be illustrated with the management of alien (exotic) invasive species: stands of ‘beautiful’ pine trees, ‘grand’ eucalypts or ‘cuddly’ introduced/extralimital fauna are embraced because of their aesthetics or the fact that they satisfy a human need (though what constitutes a ‘need’ or ‘want’ could be debated).

Similarly, funding is poured into the protection of large charismatic species at the expense of those which may play a greater role in a functioning ecosystem.

Yet it is bizarre and even naive to remain in a state of denial about the primacy of beauty appreciation to the human urge. It motivates people’s engagement with nature and desire to conserve. Likewise, to suggest that people would somehow look beyond nature’s usefulness to them in rationalizing its value is folly. How can we respond to repeated calls for conveying the importance, wonder and relevance of biodiversity to the general public (see e.g. Nabhan 1995; Miller 2005) if nature’s conservation value is to be viewed as being so separated from human identity, needs, and aspirations?

Conservation scientists may spurn the concept of ecosystem services on the one hand but yet seemingly overlook the fact that these are more than a limited set of provisioning and regulating services. They include all benefits from nature, wherein cultural services – e.g. recreation and health, aesthetic appreciation, heritage, artistic and spiritual values – are integral to many people’s lives, scientists included.

Cultural services also include education and scientific values. Have conservation scientists forgotten that biological diversity is valuable in its usefulness to sustaining our own professions and research? As detached scientists, do we see ourselves separate from the people who rely daily on ecosystem services, use the recreation value of nature as places to spend time with family or to seek inspiration for our writing, or to make a living conducting field research?

Agreed, the beauty of nature should not be the sole reason for conserving biodiversity. Neither should its usefulness to humans – inclusive of the derived cultural and spiritual dimensions – solely determine the value of biodiversity. This view would be equally disastrous for biodiversity (assuming current ethical orientations remain unchanged).

Despite humanity’s circular efforts to continuously seek out ‘all or nothing’ scenarios or ‘silver bullet’ solutions, the answer is always one of balance and blend. And it is always dependent on context.

Context is Critical

In this respect, the usefulness of some insights derived from Rudd’s (2011) study could be questioned, and indeed the value of all such global studies which seek to find broad-scale trends and generalizations. Inevitably, the context and reasoning for why scientists agreed for statements in the way they did is non-transparent and thus open to misinterpretation.

Responses to the survey statements are likely to be highly dependent on the respondent’s own reference context. Opinions will vary according to whether one’s point of reference is in semi-urban North America or semi-rural Southern Africa.

Indeed, in answering some of the survey statements, it would be easy to say “Well, it depends…” That is not fence-sitting – it is an appreciation of context as a determinant of opinion regarding conservation solutions, especially those where values and moral judgement are involved (is that all of them?). Naturally, there are general principles which might underpin particular strategies but, in most cases, context prevails. To be fair, Rudd’s study appears to have found a high level of importance given to context–dependent understanding of how people and nature interact.

Context is tricky. For example, was the global shift to whale conservation primarily motivated by knowledge of the whale’s role in supporting ecosystem function? Was it because of its usefulness to humans? Was it the whale’s beauty? Was it their cultural or spiritual value? It might have been all this and more – and emphasis would have shifted across cultures, countries and demographics.

Alien (exotic) invasive species, arguably the world’s most severe conservation issue, is another example. Their historic introduction was largely based on their perceived usefulness (utility), beauty and cultural value to humans. Objections to their removal are often contested on the same grounds. Many people have also developed meaningful interactions with this exotic nature (e.g. pine trees on South Africa’s Table Mountain), yet in many cases such species are highly disruptive to ecosystem function. Clearly, multiple values and priorities are at play, which are again context-specific.

Rhinos and lions are slaughtered for their horns and genitals to satisfy a utilitarian ‘need’ as aphrodisiacs. Yet the same utilitarianism packaged as tourist appreciation or existence value supports their conservation. When it comes to saving species, particularly charismatic ones, ecosystem function is a hard sell. Yet, in the case of the less trendy dung beetle, it may be the best argument we have.

In promoting conservation, we need to let context inform which values need to be engaged and to equally recognize that reframing environmental messages to be aligned with those people’s values may tap into unexplored opportunities for conservation and pro-environmental behaviour (Schultz & Zelezny 2003; Cocks et al. 2012).

From Part of the Problem…

The extent to which we should be alarmed by the outcomes of Rudd’s (2011) survey is dependent on interpretations for conservation policy and practice. On the one hand, the overall results indicate a biocentric value orientation amongst conservation scientists which, in the interest of global biodiversity, appears positive.

On the other hand, the results may be indicative of a failure of conservation science to appreciate which values and motivations are more likely to foster environmentally responsible behaviour (ERB) in society. Equally, it may infer a tacit resistance to value systems which do not conform to their own, despite a cognitive desire to remain value-free and objective. Science is a culture with its own norms, values, beliefs and taboos.

Do scientists’ opinions provide evidence to support the uncomfortable notion that, even as conservationists, we may be ironically part of the same perceptual disconnect which we regularly write about as being at the heart of the biodiversity crisis? Do we not see ourselves as part of nature? Do we not see our own everyday actions connected to – and contributing toward – the very biodiversity loss which concerns us?

Bizarrely, one-third of surveyed scientists disagreed that “Biodiversity should be conserved to ensure human survival” (23rd ; MA = 19.3%; LA = 32.8%; n = 1162). How does that work exactly? Does that mean as the selfless scientist we are ready to sacrifice our own survival for the benefit of biodiversity? Do we see ourselves immune from human die out? Or is it a question of numbers, scale and who is involved?

Conservation initiatives fail when people feel alienated (Pyle 2003). Given that Rudd’s (2011) results appear to distance motivating human values, they provide little confidence that the conservation sciences are likely to rapidly adopt more participatory and inclusive approaches which are open to a plurality of values and which will engage our constituencies. Furthermore, without tapping into these human (cultural, spiritual and utilitarian) dimensions, we are less likely to convince the public about whether conservation should be supported at all (cf. Zaradic et al. 2009)

There may be hope. Rudd (2011) concludes that given the relative consensus on the severity of the loss of biological diversity, “scientists may be willing to discuss potentially contentious conservation options”. We can only anticipate that those alternatives will emerge from broader worldviews than exhibited in the survey’s findings, such that “contentious” extends to giving greater weight to the anthro- and eco-centric dimensions of the social-ecological system and how they might be utilised to change human behaviour. Will the conservation mainstream recognise that, in some cases, cultural and spiritual values may be the best motivation we have for encouraging holistic biodiversity conservation?

…To Part of the Solution

The scientists were in significant agreement with the statement “People be should be made to change their behaviour to conserve species and ecosystem” (11th , MA = 31.1%, LA = 18.9%; n = 1169).

Conservation is about behaviour (Schultz 2011). And in this there is much agreement. Collectively, society needs to dramatically modify their actions toward the natural environment. But can people be “made” to change their behaviour? This appears to be an antiquated assertion which fails to recognize that coercion is rarely a recipe for long-term conservation success.

People interact with nature in important ways which are either poorly understood or unrecognized. Motivations for why people desire to conserve biodiversity are as complex as they are diverse. A willingness to understand these factors across specific contexts is critical, as is a willingness to remain open to guiding motivations which may not align with our own.

If people do not see nature as being beneficial to themselves, then why would they care to conserve it? We know of few public conservation donors, volunteers, or other enthusiasts who would state that their motivation and commitment to biodiversity is because it sustains ecosystem function. Can they be “made” to believe that it is of importance to them? For better or worse, we are conversely driven by emotion, meaning, utility and the experiential elements of our interactions with nature, regardless of whether we consider that to be morally correct.

Improved education and awareness is needed to redress the balance and improve eco-literacy as a basis for understanding of ecological systems, their functioning and the interconnections between biodiversity. But we cannot expect that such knowledge will ever displace the more affective and sensorial dimensions from which we derive satisfaction, security, and well-being. The cognitive and affective dimensions are two sides of the same coin – the ying and yang. In addition, in the absence of scientific eco-literacy and education (i.e. unavailable to most of the global populace), cultural, spiritual and utilitarian values may be all we can rely on to motivate conservation.

The ecosystem service concept has flaws in its current application, particularly an overemphasis on economic valuation and/or measuring the ecological capacity of ecosystems to provide services. Additionally, the public does not know what it means. However, the concept holds potential in communicating the fundamental links between nature and human well-being to broader society. It has value in making explicit that biodiversity is not stand alone but is the fabric which underpins human existence and the everyday benefits derived.

Greater efforts need to be directed toward communicating ecosystem services in the mainstream, though nuanced toward multiple value orientations. Chiefly, the inextricable interconnectedness of our social-ecological systems at multiple scales must be accentuated at every opportunity.

Meaningful Nature Experience: A Way Forward?

Value is a human construct. However, even if we can argue that value of biodiversity is not necessarily dependent on people, we must acknowledge that but biodiversity conservation is. The greater the value people attach to it, the greater its chance of survival. This is the critical distinction that needs to be made. Value is accumulated and cultivated through direct meaningful lived experience.

If we are to understand how people and nature interact in particular places, we have to be equally open to the fact that interaction may have a spiritual or cultural dimension.

For example, studies have found that peak experience in wilderness areas fosters spiritual expression through valuing the natural environment as sacred as well as in formulating new meaning and perceived connections with the powerful hidden forces of wild nature (McDonald et al. 2008). These links are considered important to both individual wilderness users (in promoting health, happiness and wellbeing) (McDonald et al. 2008) and for providing experiential justification for why conservation of those areas and others should be supported at all (Zaradic et al. 2009).

These experiences surpass an intellectual interest in nature; they create an affective bond which allows people to feel an interconnected part of nature. When one truly feels part of nature, one appreciates the integrity of the implicit and unbroken wholeness of the social-ecological system. This includes equal appreciation for utilitarian benefits alongside the ecological function. One comes to know that every piece of biological diversity plays an important part in the process, humans included. Connectedness with nature fuels pro-conservation behaviour.

Such notions often tend to sound fanciful and far-fetched as realistic ways forward. But the fact is global conservation is at impasse with respect to how to enact change – and seemingly exhausting most conventional ‘solutions’. It would be reassuring to think that “scientists may be willing to discuss potentially contentious conservation options” (Rudd 2011). Only then, can we agree with Rudd’s (2011) further conclusion that “we could be on the cusp of a period of evolution in thinking about how conservation goals might be redefined.”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

“Managers who are trained in the physical and biological sciences may be inclined to ignore or discount the spiritual values of people who oppose their management efforts, because such values seem inconsistent with a scientific understanding of the resources. There is a tendency to regard spiritual value as a recreational “amenity” — a somewhat frivolous side issue next to the “real” concerns of hard science and economics. Arguing that spiritual values do not have a basis in traditional science does not, however, in any way diminish their power to motivate people… a threat to the existence of wild nature is a threat to the central spiritual value of many people’s lives.” (Schroeder 1991: 5)

Citation/Written by:

Zylstra, M. J. 2012. Paradoxical scientific priorities and values in biodiversity conservation. eyes4earth.org. URL: http://eyes4earth.org/paradoxical-priorities/

Excerpts of this text will be refined for inclusion in Zylstra’s PhD thesis on meaningful nature experiences.

References:

Be the first to share a comment